Original French: cõcave, comme le tige de Smyrniũ Olus atrũ, Febues, & Gentiane:

Modern French: concave, comme le tige de Smyrnium Olus atrum, Febves, & Gentiane:

Among plants in some way similar to Pantagruelion, referred to throughout Chapter 49.

Notes

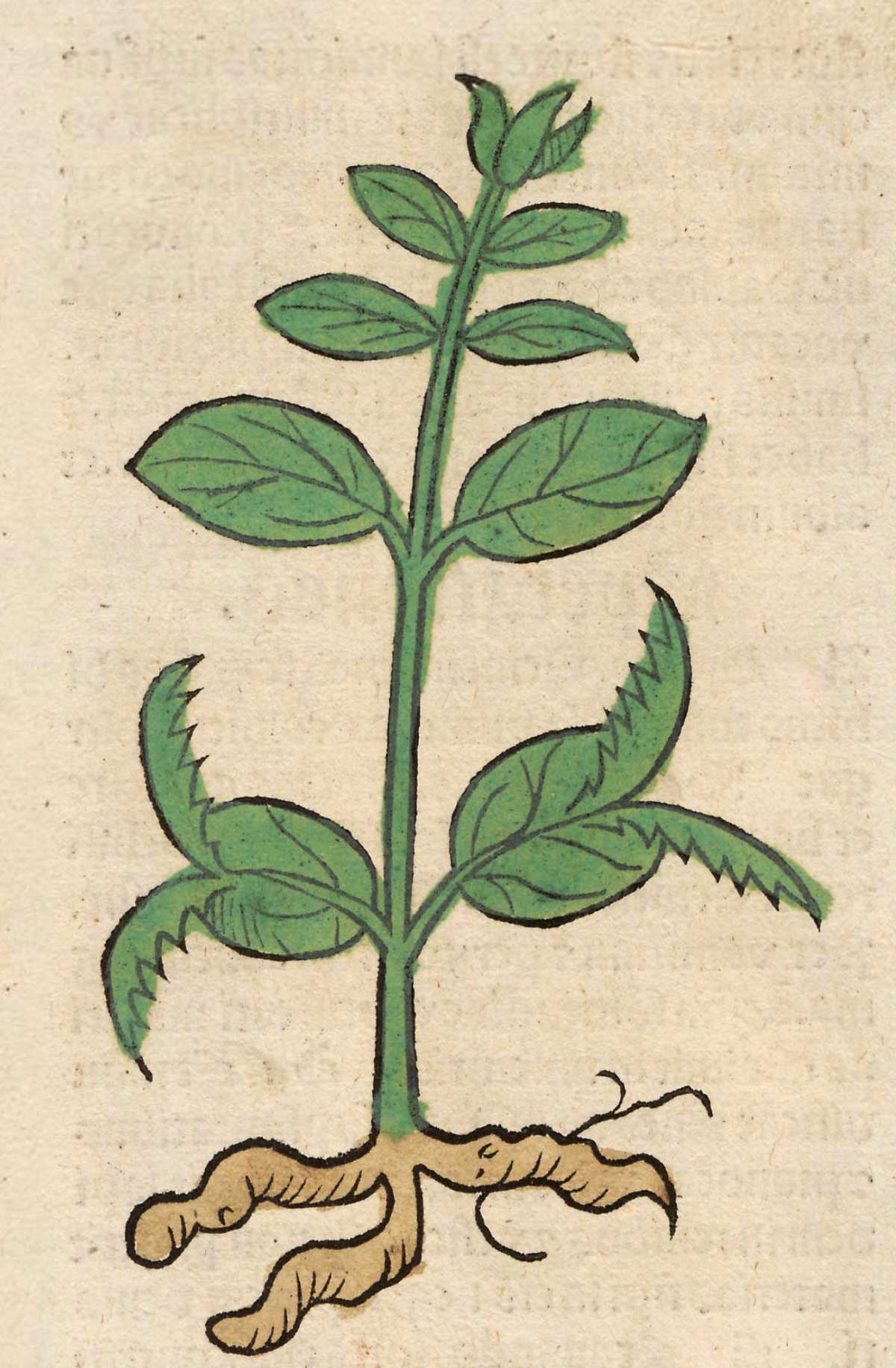

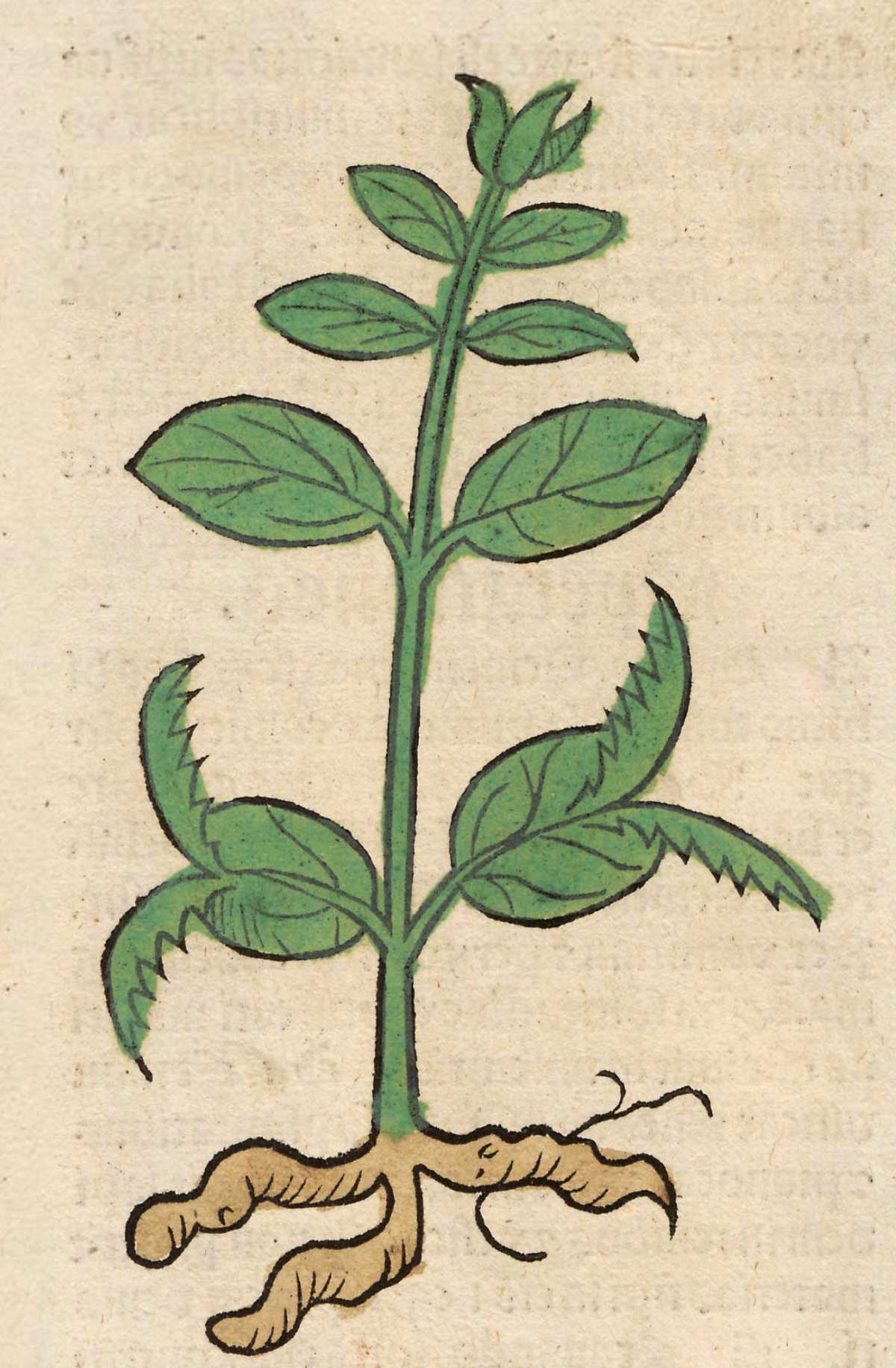

Genciana

Genciana (text)

Gentiana

Gentiana acaulis L.

Gentiana V Gentianella major verna

Clusius, Carolus (1526-1609),

Rariorum plantarum historia vol. 1. Antverpiae: Joannem Moretum, 1601. fasicle 3, p. 314.

Plantillustrations.org

Smyrnium olusatrum

Zorn, Johannes (1739–1799), Icones plantarum medicinalium. Nuremberg: 1779-1790. Plate 592.

Smyrnium olusatrum

Smyrnium olusatrum L.

Riserva naturale Monte Pellegrino Palermo, Sicily

smyrnium, olus atrum

Sed praecipue olusatrum mirae naturae est; hipposelinum Graeci vocant, alii zmyrnium. e lacrima caulis sui nascitur, seritur et radice. sucum eius qui colligunt murrae saporem habere dicunt, auctorque est Theophrastus murra sata natum.

A herb of exceptionally remarkable nature is black-herb [Our alexanders], the Greek name for which is horse parsley, and which others call zmyrnium. It is reproduced from the gum that trickles from its own stalk, but it can also be grown from a root. The people who collect its juice say that it tastes like myrrh, and Theophrastus [Hist. Plant. IX] states that it sprang first from sown myrrh seed.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 5: Books 17–19. Harris Rackham (1868–1944), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1950. 19.48.

Loeb Classical Library

olus atrum

Olusatrum, quod hipposelinum vocant, adversatur scorpionibus. poto semine torminibus et interaneis medetur, idem difficultatibus urinae semen eius decoctum ex mulso potum. radix eius in vino decocta calculos pellit et lumborum ac lateris dolores. canis rabiosi morsibus potum et inlitum medetur. sucus eius algentes calefacit potus. quartum genus ex eodem aliqui faciunt oreoselinum, palmum alto frutice recto, semine cumino simili, urinae et menstruis efficax.

Olusatrum (alexanders), also called hipposelinum (horse parsley), is antipathetic to scorpions. Its seed taken in drink cures colic and intestinal worms. The seed too, boiled and drunk in honey wine, cures dysuria. Its root, boiled in wine, expels stone, besides curing lumbago and pains in the side. Taken in drink and applied as liniment it cures the bite of a mad dog. A draught of its juices warms those who have been chilled. A fourth kind of parsley is made by some authorities out of oreoselinum (mountain parsley), a straight shrub a palm high, with a seed like cummin, beneficial to the urine and the menses.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 6: Books 20–23. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1951. 20.46.

Loeb Classical Library

smyrnium, olus atrum

Smyrnion caulem habet apii, folia latiora et maxime circa stolones multos quorum a sinu exiliunt, pinguia et ad terram infracta, odore medicato cum quadam acrimonia iucundo, colore in luteum languescente capitibus caulium orbiculatis ut apii, semine rotundo nigroque; arescit incipiente aestate. radix quoque odorata gustu acri mordet, sucosa, mollis. cortex eius foris niger, intus pallidus. odor murrae habet qualitatem, unde et nomen. nascitur et in saxosis collibus et in terrenis. usus eius calfacere, extenuare. urinam et menses cient folia et radix et semen, alvum sistit radix, collectiones et suppurationes non veteres item duritias discutit inlita. prodest et contra phalangia ac serpentes admixto cachry aut polio aut melissophyllo in vino pota, sed particulatim, quoniam universitate vomitionem movet: qua de causa aliquando cum ruta datur. medetur tussi et orthopnoeae semen vel radix, item thoracis aut lienis aut renium aut vesicae vitiis, radix autem ruptis, convolsis. partus quoque adiuvat et secundas pellit. datur et ischiadicis cum crethmo in vino. sudores ciet et ructus, ideo inflationem stomachi discutit, vulnera ad cicatricem perducit. exprimitur et sucus radici utilis feminis et thoracis praecordiorumque desideriis, calfacit enim et concoquit et purgat. semen peculiariter hydropicis datur potu, quibus et sucus inlinitur. et ad malagmata cortice arido et ad obsonia utuntur cum mulso et oleo et garo, maxime in elixis carnibus. sinon concoctiones facit sapore simillima piperi. eadem in dolore stomachi efficax.

Smyrnion has a stem like that of celery [Perhaps “parsley”], and rather broad leaves, which grow mostly about its many shoots, from the curve of which they spring; they are juicy,e bending towards the ground, and with a drug-like smell not unpleasing with a sort of sharpness. The colour shades off to yellow; the heads of the stems are umbellate, as are those of celery; the seed is round and black. It withers at the beginning of summer. The root too has a smell, and a sharp, biting taste, being soft and full of juice. Its skin is dark oh the outside, but the inside is pale. The smell has the character of myrrh, whence too the plant gets its name. It grows on rocky hills, and also on those with plenty of earth. It is used for warming and for reducing. Leaves, root, and seed are diuretic and emmenagogues. The root binds the bowels, and an application of it disperses gatherings and suppurations, if not chronic, as well as indurations; mixed with cachry, polium, or melissophyllum, it is also taken in wine to counteract the poison of spiders and serpents, but only a little at a time, for if taken all at once it acts as an emetic, and so is sometimes given with rue. Seed or root is a remedy for cough and orthopnoea, also for affections of thorax, spleen, kidneys or bladder, and the root is for ruptures and sprains; it also facilitates delivery and brings away the after-birth. In wine with crethmos it is also given for sciatica. It promotes sweating and belching, and therefore dispels flatulence of the stomach. It causes wounds to cicatrize. There is also extracted from the root a juice useful for female ailments, and for affections of the thorax and of the hypochondria, for it is warming, digestive and cleansing. The seed is given in drink, especially for dropsy, for which the juice also is used as liniment. The dried skin is used in plasters, and also as a side-dish with honey wine, oil and garum, especially when the meat is boiled. Sinon tastes very like pepper and aids digestion. It also is very good for pain in the stomach.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 7: Books 24–27. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1956. 27.109.

Loeb Classical Library

olusatrum

Elaphoboscon ferulaceum est, geniculatum digiti crassitudine, semine corymbis dependentibus silis effigie, set non amaris, foliis olusatri.

Elaphoboscon (wild parsnip) is a plant like fennel-giant, with a jointed stem of the thickness of a finger, the seed in clusters hanging down like hartwort, but not bitter, and with the leaves of olusatrum [Alexanders].

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 6: Books 20–23. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1951. 22.37.

Loeb Classical Library

Smyrnium

Pliny xvii c. 10 (103?)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

Olus atrum

Pliny xix, 8

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

concave

Creuse. La tige du chanvre est en effet fistuleuse.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 339.

Internet Archive

smyrnium, olus atrum

Ne faut-il point réunir ces deux mots en un seul, Smyrnium ousatrum ? Le maceron, Smyrnium olusatrum L., est une ombellifère, jadis utilisée en matière médicale. Il se peut cependant que Rabelais ait distingué deux espèces, car on trouve en France deux autres espèces de Smyrnium. L’olusatrum de Pline, ou hipposelinon ou smyrnion est le 3 L. Cf. Pline, XIX, 48; XX, 46; XXVII, 109. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 339.

Internet Archive

febves

Fève, Faba vulgaris Mœnch., Papilionacée. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 339.

Internet Archive

smyrnium, olus atrum

Plusieurs éditeurs ont proposé de réunir en un seul mot Smyrnium olusatrum; il s’agirait du mauron, variété d’ombellifère utilisée autrefois comme remède.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Pierre Michel, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1966. p. 552.

olus atrum

Le maceron, ombellifère utilisée en pharmacie.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 501 n. 1.

gentiane

gentian. Forms: jencian, gencyan , gencian, gentiane, gentian. [adaptation of Latin gentiana, so called (according to Pliny) after Gentius, king of Illyria.]

Any plant belonging to the genus Gentiana (compare felwort); esp. G. lutea, the officinal gentian which yields the gentian-root of the pharmacopoeia.

C. 1000 [see felwort].

1382 [see gentian-tree in 2].

C. 1400 Lanfranc’s Cirurg. 61 Take þe pouder of crabbis brent vj parties, gencian iij parties… make poudre.

1516 Life St. Bridget in Myrr. our Ladye p. lii, Gencian whiche is a moch bytter erbe she helde contynually in hir mouth.

1597 John Gerard (or Gerarde) The herball, or general historie of plants ii. cv. (1633) 432 There be divers sorts of Gentians or Felwoorts.

1671 Salmon Syn. Med. iii. xxii. 402 Gentian, the root resists poyson and Plague.

1801 Southey Thalaba iv. xxiv, The herbs so fair to eye Were Senna, and the Gentian’s blossom blue.

1830 Lindley Natural Syst. Botany 216 The intense bitterness of the Gentian is a characteristic of the whole order.

attributive, as in gentian-blue, -flower, -root, -tree, -violet, -water, -wine; gentian-bitter, the tonic principle extracted from gentian root; gentian-worts, Lindley’s name for the N.O. Gentianaceæ.

1382 John Wyclif Jer. xvii. 6 It shal ben as iencian trees [Latin myricæ] in desert.

1865 Baring-Gould Werewolves vii. 85 Sand-hills… patched with gentian-blue.

1530 Palsgr. 224/2 Gencyan rote, gentian.

A. 1700 B. E. Dict. Cant. Crew, Gentian-wine, Drank for a Whet before Dinner.

Smyrna

Smyrna. [A place-name; Latin Smyrna, Greek Smurna.]

The chief port of Asia Minor, situated at the head of the gulf of the same name, used attributive in the names of various things produced in the vicinity of or connected with the city, as Smyrna carpet, cotton, earth, fig, kingfisher, opium, rug, runt, wheat.

1735 J. Moore Columbarium 44 The Smyrna Runt… is middle siz’d and feather-footed.

1753 Ephriam Chambers Cyclopædia; or, an universal dictionary of arts and sciences, Supplement, Saponacea terra,… a kind of native alkali salt, of the nature of the nitre,… called by some Smyrna earth.

1753 Ephriam Chambers Cyclopædia; or, an universal dictionary of arts and sciences s.v. Wheat, Suppl., Smyrna Wheat, a peculiar kind of Wheat that has an extremely large ear.

1840 Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge XVII. 203/2 The physical characters of the best Smyrna opium.

1877 Encyclopædia Britannica VI. 482/2 One of these [Indian cottons] is cultivated to a considerable extent in the Levant, and is known in the market as Smyrna cotton.

Smyrnium olusatrum

Smyrnium olusatrum L., common name Alexanders is a cultivated flowering plant, belonging to the family Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae). It is also known as alisanders, horse parsley and smyrnium. It was known to Theophrastus (9.1) and Pliny the Elder (N.H. 19.48).

In the correct conditions, Alexanders will grow 120 to 150 cm tall, with a solid stem that becomes hollow with age. The leaves are bluntly toothed, the segments ternately divided the segments flat, not fleshy.

Alexanders is native to the Mediterranean but is able to thrive farther north. The flowers are yellow-green in colour, and its fruits are black. Alexanders is intermediate in flavor between celery and parsley. It was once used in many dishes, either blanched or not, but it has now been replaced by celery. It was also used as a medicinal herb. It is now almost forgotten as a food source, although it still grows wild in many parts of Europe, including Britain. It is common among the sites of medieval monastery gardens.