Original French: le Poupié, aux Dents:

Modern French: le Poupié, aux Dents:

Notes

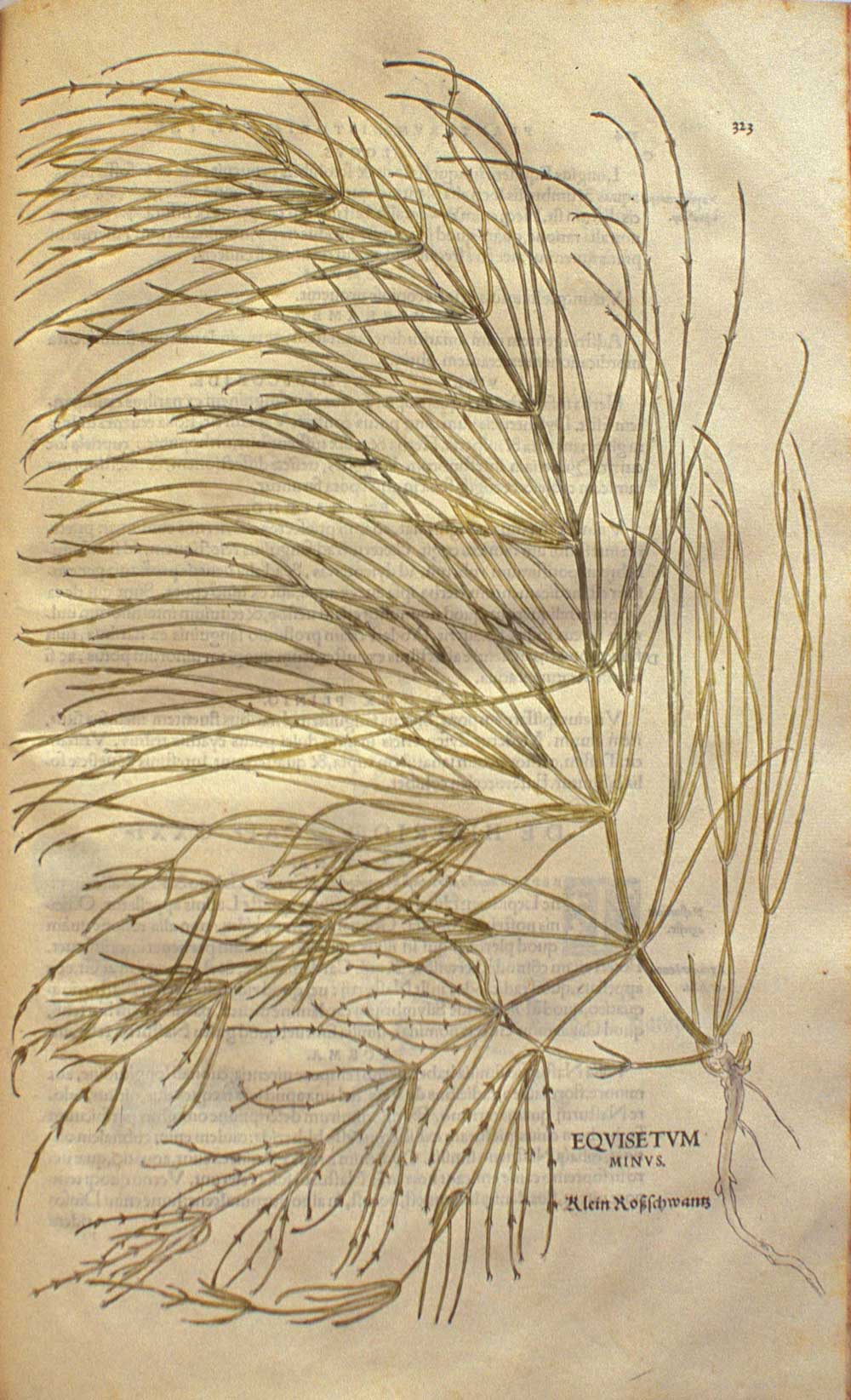

Portulaca

Portulaca oleracea

purslane

Purslane to the Teeth

Pliny (xx. 20, § 81) makes this plant good for teeth, Cabbage and Gum-plants (xx. 9, § 36; xxiv. 11, § 64) injurious to teeth.

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

le Poupié, aux Dents

Est et porcillaca quam peplin vocant, non multum sativa efficacior cuius memorabiles usus traduntur: sagittarum venena et serpentium haemorrhoidum et presterum restingui pro cibo sumpta et plagis inposita extrahi, item hyoscyami pota e passo expresso suco. cum ipsa non est, semen eius simili effectu prodest. resistit et aquarum vitiis, capitis dolori ulceribusque in vino tusa et inposita, reliqua ulcera commanducata cum melle sanat. sic et infantium cerebro inponitur umbilicoque prociduo, in epiphoris vero omnium fronti temporibusque cum polenta, sed ipsis oculis e lacte et melle, eadem, si procidant oculi, foliis tritis cum corticibus fabae, pusulis cum polenta et sale et aceto. ulcera oris tumoremque gingivarum commanducata cruda sedat, item dentium dolores, tonsillarum ulcera sucus decoctae. quidam adiecere paulum murrae. nam mobiles dentes stabilit conmanducata, vocemque firmat et sitim arcet. cervicis dolores cum galla et lini semine et melle pari mensura sedat, mammarum vitia cum melle aut Cimolia creta, salutaris et suspiriosis semine cum melle hausto. stomachum in acetariis sumpta corroborat. ardenti febribus inponitur cum polenta, et alias manducata refrigerat etiam intestina. vomitiones sistit. dysinteriae et vomicis estur ex aceto vel bibitur cum cumino, tenesmis autem cocta. comitialibus cibo vel potu prodest, purgationibus mulierum acetabuli mensura in sapa, podagris calidis cum sale inlita et sacro igni. sucus eius potus renes iuvat ac vesicas, ventris animalia pellit. ad vulnerum dolores ex oleo cum polenta inponitur. nervorum duritias emollit. Metrodorus, qui ἐπιτομὴν ῥιζοτομουμένων scripsit, purgationibus a partu dandam censuit. venerem inhibet venerisque somnia. praetorii viri pater est, Hispaniae princeps, quem scio propter inpetibiles uvae morbos radicem eius filo suspensam e collo gerere praeterquam in balineis, ita liberatum incommodo omni. quin etiam inveni apud auctores caput inlitum ea destillationem anno toto non sentire. oculos tamen hebetare putatur.

There is also a type of purslane, called peplis [Euphorbia peplis], being not much more beneficial than the cultivated variety, of which are recorded remarkable benefits; that the poison of arrows and of the serpents haemorrhoïs and prester are counteracted if peplis be taken as food, and if it be applied to the wound, the poison is drawn out; likewise the poison of henbane if peplis be taken in raisin wine, after extraction of the juice. When the plant itself is not available, its seed has a similarly beneficial effect. It also counteracts the impurities of water, and if pounded and applied in wine it cures headache and sores on the head; other sores it heals if chewed and applied with honey. So prepared it is applied also to the cranium of infants, and to an umbilical hernia; for eye-fluxes in persons of all ages, with pearl barley, to the forehead and temples, but to the eyes themselves in milk and honey; also, if the eyes should fall forwards [aSymptom of an obscure disease, now perhaps unknown], pounded leaves are applied with bean husks, to blisters with pearl barley, salt and vinegar. Sores in the mouth and gumboils are relieved by chewing it raw; tooth-ache likewise and sore tonsils by the juice of the boiled plant, to which some have added a little myrrh. But to chew it makes firm loose teeth, strengthens the voice and keeps away thirst. Pains at the back of the neck are relieved by it with equal parts of gall nut, linseed and honey, complaints of the breasts with honey or Cimolianc chalk, while asthma is alleviated by a draught of the seed with honey. Taken in salad it strengthens the stomach. It is applied with pearl barley to reduce high temperature, and besides this when chewed it also cools the intestines. It arrests vomiting. For dysentery and abscesses it is eaten in vinegar or taken in drink with cummin, and for tenesmus it is boiled. Whether eaten or drunk it is good for epilepsy, for menstruation if one acetabulum be taken in concentrated must, for hot gout and erysipelas if applied with salt. A draught of its juice helps the kidneys and the bladder, expelling also intestinal parasites. For the pain of wounds it is applied in oil with pearl barley. It softens indurations of the sinews. Metrodorus, author of Compendium of Prescriptions from Roots, was of opinion that it should be given after delivery to aid the after-birth. It checks lust and amorous dreams. A Spanish prince, father of a man of praetorian rank, because of unbearable disease of the uvula, to my knowledge carries except in the bath a root of peplis hung round his neck by a thread, being in this way relieved of all inconvenience. Moreover, I have found in my authorities that the head rubbed with peplis ointment is free from catarrh the whole year. It is supposed however to weaken the eyesight.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 6: Books 20–23. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1951. 20.81.

Loeb Classical Library

cabbage to teeth

Ex omnibus brassicae generibus suavissima est cyma, etsi inutilis habetur, difficilis in concoquendo et renibus contraria. illud quoque non est omittendum, aquam decoctae ad tot usus laudatam faetere humi effusam. stirpium brassicae aridorum cinis inter caustica intellegitur, ad coxendicum dolores cum adipe vetusto, at cum lasere et aceto instar psilotri evulsis inlitus pilis nasci alios prohibet. bibitur et cum oleo subfervefactus vel per se elixus ad convolsa et rupta intus lapsoque ex alto. nulla ergo sunt crimina brassicae? immo vero apud eosdem animae gravitatem facere, dentibus et gingivis nocere. et in Aegypto propter amaritudinem non estur.

Of all the varieties of cabbage the most pleasant-tasted is cyma [Broccoli], although it is thought to be unwholesome, being difficult of digestion and bad for the kidneys. Further, we must not forget that the water in which it has been boiled, though praised for its many uses, has a foul smell when poured out on the ground. The ash of dried cabbage-stalks is understood to be caustic, and with stale grease is used for sciatica, but with silphium and vinegar, applied as a depilatory, it prevents the growth of other hair in place of that pulled out. It is also taken lukewarm in oil, or boiled in water by itself, for convulsions, internal ruptures, and falls from a height. Has cabbage then no faults to be charged with? Nay, we find in the same authors that it makes the breath foul and harms teeth and gums. In Egypt too, because of its bitterness, it is not eaten.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 6: Books 20–23. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1951. 20.35.

Loeb Classical Library

le Poupié, aux Dents:

Cummium genera diximus. in his maiores effectus melioris cuiusque erunt. dentibus inutiles sunt, sanguinem coagulant et ideo reicientibus sanguinem prosunt, item ambustis, arteriae vitiis inutiles, urinam cient, amaritudines hebetant.

I have mentioned the different kinds of gums [Book XIII. §§ 66 ff]. The better the sort of each kind the more potent its effect. Gums are injurious to the teeth, coagulate blood and therefore benefit those who spit blood; they are also good for burns though bad for affections of the trachea; they promote urine and lessen the bitter taste in things.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD),

The Natural History. Volume 7: Books 24–27. William Henry Samuel Jones (1876–1963), translator. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1956. 24.64.

Loeb Classical Library

le poupié aux dents

Rabelais a mal lu: «Mobiles dentes stabilit commanducata [porcilaca]» dit au contraire Pline, XX, 81. «Commanducata dentium stupores sedat», écrit aussi Dioscoride, II, 117. Il est à noter que ce sont là vertus attribuées au pourpier cultivé, Portulaca oleracea, L., mais Pline les insère, par erreur, au chapitre de son Porcilaca, peplis ou pourpier sauvage, qui est Euphorbia peplis, L., plante au latex âcre et corrosif. Au reste, le pourpiuer n’a pas plus d’action sur les dents et gencives que les autres salades. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 361.

Internet Archive

Nenuphar…

Encore une fois, la plupart de ces exemples se retrouvent dans le De latinis nominibus de Charles Estienne. Le nenufar et la semence de saule sont des antiaphrodisiaques. La ferula servait, dans l’Antiquité, à fustiger les écoliers (cf. Martial, X, 62-10).

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique. Michael A. Screech (b. 1926), editor. Paris-Genève: Librarie Droz, 1964.

le Poupié, aux Dents:

Le pourpier, au contraire, affermit les dents (Pline, XX, lxxxi).

Rabelais, François (ca. 1483–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 506, n. 6.