Original French: Rhabarbe, du fleuue Barbare nommé Rha comme atteſte Ammianus:

Modern French: Rhabarbe, du fleuve Barbare nommé Rha comme atteste Ammianus:

Notes

La barbare

Quand la Barbare en ses habitz plus beaux

Veut demonstrer sa grand magnificence,

Fourree ainsi elle est de riches peaux,

Que ce pourtrait le met en apparence.

Desprez, François (1525-1580),

Recueil de la diversité des habits. qui sont de present en usage, tant es pays d’Europe, Asie, Affrique, & Isles sauvages, Le tout fait apres le naturel. Paris: Richard Breton, 1564. f. 134.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Le barbare

Les Barbares ont le vestement semblable

Comme tu vois, cela est tout notoire,

Quoy que te soit cest habit admirable,

La verité te constraint de le croire

Desprez, François (1525-1580),

Recueil de la diversité des habits. qui sont de present en usage, tant es pays d’Europe, Asie, Affrique, & Isles sauvages, Le tout fait apres le naturel. Paris: Richard Breton, 1564. f. 137.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

rubarbe

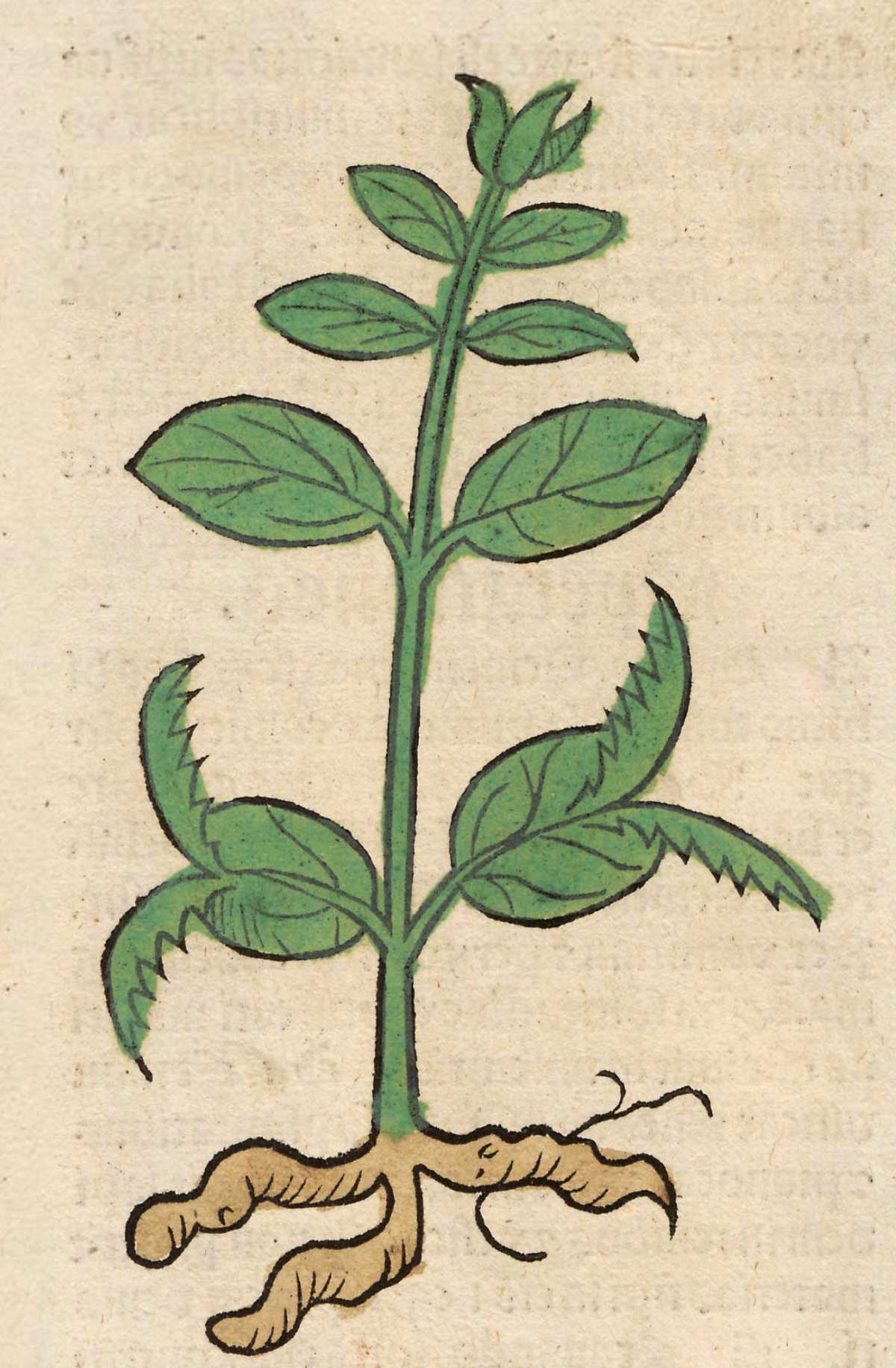

Rhabarbarum florens

Fowering Rubarbe

Gerard, John (1545-1611 or 1612),

Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes. London: John Norton, 1597.

Internet Archive

Ammianus, Roman History, Book 22, Chapter 8

26. Behind them lie the inhabitants of the Cimmerian Bosphorus, living in cities founded by the Milesiani, the chief of which is Panticapaeum, which is on the Bog, a river of great size, both from its natural waters and the streams which fall into it.

27. Then for a great distance the Amazons stretch as far as the Caspian sea; occupying the banks of the Don, which rises in Mount Caucasus, and proceeds in a winding course, separating Asia from Europe, and falls into the swampy sea of Azov.

28. Near to this is the Rha, on the banks of which grows a vegetable of the same name, which is useful as a remedy for many diseases.

Rha

Rha = Volga

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

Ammianus

Amm. Marc. xxii. 8, 28

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553),

The Five Books and Minor Writings. Volume 1: Books I-III. William Francis Smith (1842–1919), translator. London: Alexader P. Watt, 1893.

Internet Archive

rhubarbe

Rhubarbe, Rheum. (Polygonée). De Rha, nom d’un fleuve cité par Ammien Marcellin, et qui est le Volga; et barbarum. Inconnue des anciens, ell est mentionée pour la première fois (Rheum barbarum) par Isidore de Séville (VIIe siècle). On trouve la forme Reubarbe dans Platearius et le Hortus sanitatis (1500). Ce produit, anciennement importé de la Perse et de la Chine, est fourni par diverses esp. de Rheum, surtout Rh. officinale, Bn. Mais la différenciation en est assez confuse, et compliquée par des hybridations. Cf. H. Baillon, Dict. des Sc. méd. de Dechambre, 3e s., t. IV, art Rhubarbe, p. 416-436. (Paul Delaunay)

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553),

Oeuvres. Édition critique. Tome Cinquieme: Tiers Livre. Abel Lefranc (1863-1952), editor. Paris: Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, 1931. p. 349.

Internet Archive

rhubarb

rhubarb, from the barbar river named Rheu, Rea or Volga, according to the testimony of Ammianus Marcellinus, the last Roman historian of importance.

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553), Complete works of Rabelais. Jacques LeClercq (1891–1971), translator. New York: Modern Library, 1936.

rhubarbarous maundarin yellagreen funkleblue windigut diodying applejack

Instead the tragic jester sobbed himself wheywhingingly sick of life on some sort of a rhubarbarous maundarin yellagreen funkleblue windigut diodying applejack squeezed from sour grapefruice and, to hear him twixt his sedimental cupslips when he had gulfed down mmmmuch too mmmmany gourds of it retching off to almost as low withswillers, who always knew notwithstanding when they had had enough and were right indignant at the wretch’s hospitality when they found to their horror they could not carry another drop, it came straight from the noble white fat, jo, openwide sat, jo, jo, her why hide that, jo jo jo, the winevat, of the most serene magyansty az archdiochesse, if she is a duck, she’s a douches, and when she has feherbour snot her fault, now is it? artstouchups, funny you’re grinning at, fancy you’re in her yet, Fanny Urinia.

rhabarbe

La source est probablement S. Champier, Gallicum pentapharmacum, Rhabarbo, Agarico, Manna, Terebinthina et Sene Gallicis constans, Lyon, 1534. Champer cite Ammien Marcellin à ce propos.

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique. Michael Andrew Screech (1926-2018), editor. Paris-Genève: Librarie Droz, 1964.

Rhabarbe, du fleuve Barbare nommé Rha

Ammien Marcellin (IVe siècle apr. J.-C.) parle de la Volga.

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553), Œuvres complètes. Mireille Huchon, editor. Paris: Gallimard, 1994. p. 504, n. 5.

le nom des regions…

Toutes ces informations sur les plantes dont le nom est d’origine géographique sont dans le livre d’Estienne, sauf sur la rhubarbe, pour laquelle Rabelais suit sans doute Ruellius, De Natura stirpium (1536), III, 2 (mêmes renseignements dans B. Chasseneuz, Catalogus gloria mindi, XII, 90). Sur «Stœchas» (Pline, XXVII, 12), le «Calloïer des Isles Hieres» (ou Stéchades), comme signe Rabelais in 1546, ne pouvait oublier cette plante; mais c’est aussi un façon de rappeler que toutes ces pages l’ont pour auteur.

Rabelais, François (1483?–1553), Le Tiers Livre. Edition critique. Jean Céard, editor. Librarie Général Français, 1995. p. 454.

rha

rha. Obsolete [late Latin, adopted from Greek ra, said to be from the ancient name Ra of the river Volga. See also rhabarbarum, rhapontic.]

Rhubarb

1578 Henry Lyte, tr. Dodoens’ Niewe herball or historie of plantes iii. x. 329 Rha is hoate in the first degree, and dry in the second.

1597 John Gerard (or Gerarde) The herball, or general historie of plants ii. lxxviii. 313 The root [of Bastard Rhubarb] is… verie like vnto the Rha of Barbarie.

rhubarb

rhubarb. Forms: rubarbe, rewbarb(e, r(h)eubarbe, rubarb, rheubarb, rembarbe, rwbarbe, rubarde, reubard(e, rubard, rebarbe, reuberbe, rhew-, ryo-, rui-, ruberb, ruybarbe, rhebarb, dial. rhubard), – rhubarb.. [adopted from Old French reu-, reo-, rubarbe, modern French rhubarbe :-Latin type *r(h)eubarbum, shortened formed on medieval Latin r(h)eubarbarum, altered by association with rhe¯um from rhabarbarum.]

The medicinal rootstock (purgative and subsequently astringent) of one or more species of Rheum grown in China and Tibet and for a long period imported into Europe through Russia and the Levant, but since 1860 direct from China; usually (e.g. in pharmaceutical and domestic use) called Turkey or Russian rhubarb, but now known commercially as East Indian or Chinese rhubarb.

C. 1400 tr. Secreta Secret., Gov. Lordsh. 70 And after of exrohand, þat ys reubard, foure peny weght, ffor þat..withdrawys þe fleume fro þe mouth of þe stomake.

1486 Bk. St. Albans b vij, Take Rasne and Rubarbe and grynde it to gedre.

A. 1533 Ld. Berners Gold. Bk. M. Aurel.

(1546) H viii b, The phisicions with a lyttell Rubarb purge many humours of the body.

1540 J. Heywood Four PP. C iii, I haue a boxe of rubarde here Whiche is as deynty as it is dere.

1580 Lyly Euphues (Arb.) 411 The roote Rubarbe, which beeinge full of choler, purgeth choler.

1594 Plat Jewell-ho. 13 All the Rubarbe, Gums, and other Aromaticall ware, are greatly sophisticated before they come to our handes.

1597 John Gerard (or Gerarde) The herball, or general historie of plants ii. lxxix. 317 The best Rubarbe is that which is brought from China fresh and newe… The second in goodnes is that which cometh from Barbarie. The last and woorst from Bosphorus and Pontus.

1605 Shakespeare Macbeth v. iii. 55 What Rubarb, Cyme, or what Purgatiue drugge Would scowre these English hence?

1626 Bacon Sylva §19 Rubarb hath manifestly..Parts that purge, and parts that bind the body.

Figuratively, as a type of bitterness or sourness.

1526 Skelton Magnyf. 2385 Nowe must I make you a lectuary softe,..With rubarbe of repentaunce in you for to rest.

1591 Harington Orl. Fur. Pref. p.v b, In verse is both goodnesse and sweetnesse, Rubarb and Sugarcandie, the pleasaunt and the profitable.

1613 Chapman Rev. Bussy D’Ambois iii. F j b, Since tis such Ruberb to you, Ile therefore search no more.

Any plant of the genus Rheum. For various species see quots. †Pontic or Pontish rhubarb = rhapontic.

A. 1400 Pistill of Susan 112 With Ruwe and Rubarbe, Ragget ariht.

1535 Boorde Let. in Introd. Knowl. (1870) 56, I haue sentt to your mastershepp the seedes off reuberbe, the which come owtt off barbary.

1578 Henry Lyte, tr. Dodoens’ Niewe herball or historie of plantes iii. x. 328 There be diuers sortes of Rha, or as it is nowe called Rheubarbe.

1597 Gerarde Herbal ii. lxxix. 317 The Ponticke Rubarbe is lesser..than that of Barbarie.

1797 Encyclopædia Britannica (ed. 3) XVI. 206/2 Rheum..1. The rhaponticum, or common rhubarb,… grows in Thrace and Scythia, but has been long in the English gardens.

rhubarb

The word ‘rhubarb’ as repeated by actors to give the impression of murmurous hubbub or conversation. Hence allusively.

1934 A. P. Herbert Holy Deadlock 194 The chorus excitedly rushed about and muttered ‘Rhubarb!’

1952 Radio Times 17 Oct. 11/3 The unemployed actors had a wonderful time. We’d huddle together in a corner and repeat `Rhubarb, rhubarb, rhubarb’ or `My fiddle, my fiddle, my fiddle’-and it sounded like a big scene from some mammoth production.

1958 Observer 7 Dec. 18/5 Actors, who shout ‘rhubarb-rhubarb-rhubarb’ to give the impression of a distant riot.

Symphorien Champier

Symphorien Champier (1471–1538), a Lyonnese doctor born in Saint-Symphorien, France. A doctor of medicine at Montpellier, Champier was the personal physician of Antoine, Duke of Lorraine, whom he followed to Italy with Louis XII, attending to several battles, and finally settling in Lyon. He worked in Lyon alongside François Rabelais (who wrote satirically of him in Gargantua and Pantagruel), where he established the College of the Doctors of Lyon. There he fulfilled the duties of an alderman and contributed to numerous local foundations, in particular L’Ecole des médecins de Lyon (“The School of the Doctors of Lyon”).

His fame was considerable in Lyon, which in the 16th century was the greatest manufacturer of medical books in France, with editors such as Sébastien Gryphe. In addition to medicinal science, Champier studied Greek and Arab scholars and composed a great number of historical works, including Chroniques de Savoie in 1516 and Vie de Bayard in 1525.

He was also associated with Renaissance occultism.